巨无霸汉堡包指数又称巨无霸指数(Big Mac index),是国际经济学最古老的理论之一,它是一个非正式的经济指数,用以测量两种货币的汇率理论上是否合理。这种测量方法假定购买力平价理论成立,汇率由同一组商品的相对价格决定。

两国的巨无霸的购买力平价汇率的计算法,是以一个国家的巨无霸以当地货币的价格,除以另一个国家的巨无霸以当地货币的价格。该商数用来跟实际的汇率比较;要是商数比汇率为低,就表示第一国货币的汇价被低估了(根据购买力平价理论);相反,要是商数比汇率为高,则第一国货币的汇价被高估了。

自首次公布以来,该指数已经成为经济学家最爱吃的一道“食品”,这是因为麦当劳在全球120个国家和地区开有分店,大汉堡的组成原料和工序在世界各地基本没有变化,可以保证同质同量。而且大汉堡虽只是一件商品,却包含了多种原料和劳动,如面包、肉类、调料和人工制作,因此也可以把它的价格看作一种综合指数。

这些数字表明两件事。首先,亚洲各国央行仍在买进美元。其次,该地区尚未克服的一个关键漏洞:对美国消费者依赖成瘾。后一点意味着亚洲不能对此次危机自鸣得意。当然,巨无霸汉堡指数是一个晴雨表,其中一些将撤去。巨无霸指数用购买力平价表示全球麦当劳公司汉堡包的比较价格。这个想法是,美元应该购买所有国家同样数额的货币,而且随着时间推移,汇率应走向和一系列商品和服务均衡的价格水平。

日本的境况不十分光明。几百亿美元的支出仅仅提供短期修正。随着中国和印度的崛起,这笔钱将一点也不会使日本接近解决稳步失去的竞争力或人口老龄化。这只会给亚洲最大的经济体增加本已艰巨的债务负担。因此,决策者们坚持一个十多年来创造奇迹的原则:限制汇率。目前(2009年)是有利于美国。美国需要亚洲的资金以资助其历史性的贷款飙升。这就是为什么亚洲购买美元存在强大惯性。

一个被低估的风险是,对冲基金经理已经投注多年的美元崩溃。这种情况将推动汇率,并在亚洲扮演可怕的逆风角色。对欧洲来说可能是一个更直接的问题。2009年的巨无霸指数显示,挪威克朗被高估了72%,接下来是瑞士法郎(68%),丹麦克朗(55%)和瑞典克朗(38%)。 同时,在许多情况下,亚洲的汇率低于雷曼崩溃前水平。对增长最快的地区来说,短期是积极的,但长期是消极的。证明无处不在——即使是在汉堡。

1、用汉堡包来判定汇率,具有相当大的局限性。因为汉堡包是贸易商品 (exchanged googds)。比起非贸易商品而言(例如房子之类),在发展中国家贸易商品的发展要快得多。所以用汉堡包来衡量发展中国家与发达国家之间的汇率水平,显然失之偏颇。另外,即使不考虑发展中国家与发达国家的发展差异,由于不同国家之间消费者对待商品的偏好是不一致的,这也会导致价格的“虚假”。对于非完全浮动汇率的国家,这种指数也是偏离实际均衡的。

2、也有不少经济学家并不觉得巨无霸是一道美餐,每次《经济学人》更新大汉堡指数时,总有人抱怨汉堡经济学没有去掉芥菜味。在他们看来,大汉堡指标其实非常片面,因为汉堡只是快餐中的一种食品,而快餐只是国民食物支出中的一小部分,而食物支出在发达国家仅占较少比重。小小汉堡并不能起到一叶知秋的作用。但如果某些国家的经济水平、文化背景、消费习惯差别不太,大汉堡指数还是可以在相当程度上反映出汇率的变动趋势的。

The Big Mac Index goes to North Korea

Cheeseburger in Paradise Island

Jun 20th 2013, 3:59 by H.T. | PYONGYANG 惊喜是不是到朝鲜的游客很可能经常遇到。指南,精心策划的行程,通常竭尽全力,以避免意外的刷与普通的朝鲜人,无论他们是卖衣服或玉米的妇女在当地的夜飞“青蛙市场”,或在当地酒吧喝酒的男人。这是一个耻辱,因为这样的遭遇,帮助一个知之甚少的人,人性化:例如,一个23岁的朝鲜腼腆地告诉我们,她是糊涂,这可能进一步去破坏定型比她与布拉德·皮特最近访问所能想象。令人高兴的是,一些非政府组织的管理要突破这种不信任的厚厚的面纱,以促进真正的参与与民主人民共和国(朝鲜)。总部设在新加坡的朝鲜王朝交流,促进人民对高飞扬的年轻专业人士和官僚朝鲜和外面的世界的人们之间的接触,是其中之一。 *近日,我前往平壤,与他们举行讨论经济与财政部和央行的成员。从开始到结束,我接触那些我处理离开我吃惊。偶尔,我留下了深刻印象。

起初,它是很难知道什么使朝鲜的金融机构。超出了我的酒店,新的中央银行,高约20层,正在兴建的大同河的河岸上。在我到达之前有人告诉我可能是杜撰的故事,中央银行家们自己做的建设工作。在一个外墙被漆成劝告的工作要做“一口气”,即一个口号,很快就完成了,像军事行动。随着货币翻滚,通胀上升和增长停滞,这战斗口号越来越多地应用到经济学。金正云年轻的独裁者,劝勉:“让我们征服的行业,像我们征服了空间,指的是去年12月的臭名昭著的卫星发射。所以,当我把我的地方,傣族人民大学习厅,盯着几十个表情严肃的经济决策者在厚厚的大衣,围巾和手套,我还以为是国家规划革命面临的冲锋队。我支撑一个非常艰难的时间。

然而,而不是超过经济学家的看法,世界经济挑战我,他们抽我的事实确凿的事实。每个会话结束时,交付的票据对我来说,无论是在英语或通过我的翻译,与来自世界各地的(我猜测)可能是有用的朝鲜几乎绝望的需求案例研究。这导致了一种微妙的舞蹈,因为该国自身的经济问题的讨论是严格的禁忌。自己似乎说了很多:“你最好告诉我们更详细的消息,强烈措辞”一说。 “我们希望更真实的例子,”另一个说。的问题,很多的话题集中在通货膨胀和货币稳定计划,地方当局的关注。 “你是如何平衡通胀和经济增长”一说。 “什么是最佳的通胀率?什么是理想的通胀目标水平,“另一个说。另一个说:“我在现实震撼般的计划,以减少在1995年墨西哥通货膨胀很感兴趣。例如,它是怎么锚定通胀预期?“不止一次,我告诉他们,只要他们有访问互联网,他们可以找出这样的问题本身的答案。这旁门左道的建议通常是会见两眼发直。但他们没有他们的理论知识不足,连我自己(非经济学家)解释:一旦能够提高我解释通货膨胀的成因。

我去朝鲜武装我自己的一些旁门左道的工具。举例来说,我认为“经济学人”巨无霸指数的幻灯片将娱乐,不只是为了引起讨论购买力平价,但更多的讨论汉堡。 (如果你相信的每日快速,运行平壤唯一的汉堡酒吧的女人是金正日的阿姨,和汉堡被称为“剁碎的肉和面包”。)金正日的父亲,金正日警惕的目光下,和他的祖父金日成,我提出的巨无霸指数(见下图)。确实有麦当劳的一个简短的讨论。但挤入更为有趣的是,中国的货币是否高估或低估的。

这家安静的货币和通胀的迷恋是可以理解的。在朝鲜生活的特殊性之一是普通人如何管理求生存,甚至在比较繁华的首都,在牙齿的一种有害的,事实上的双货币系统。据官方统计,在我住的酒店是100韩元对美元汇率。在超市里卖的一切从乒乓球拍内衣浴室套房(所有从中国进口的),一个女人在我面前让我震惊由剥落结帐票据110000韩元。这时我才意识到,她(灰色市场)汇率,固定在一个不显眼的窗口后面结帐,为8000韩元对美元。进口危地马拉咖啡一杯,可能会花费几元钱,我和她。但一个大学讲师,我跟,它会代表超过一个月的薪水的官方汇率使用韩元,他赢得。难怪他可以不记得上一次他带着一个女孩出去约会。他说,他非常感谢物资交给居委会,使人们能够得到如此低的工资制度。但那些谁能够获得美元,因此可以买到便宜的咖啡,酒精,寿司,牛排和汽车,和那些谁不之间的不平等,是比大同河更宽。很多人在我的讲座耙薄(虽然妇女们穿着无可挑剔)。我无法找出他们吃什么,吃午饭,因为我们没有一起吃。

毫无疑问,参加研讨会的部分特权的精英,但没有特权。他们穿着沉重的冬季齿轮在春末,因为他们简直冰寒通过讲座,因为他们坐在海绵体大厅。只有我获得了一笔小额加热器要注意保暖,这是隐藏背后的讲台。一名成员的观众谁不知道我有这个特权来告诉我,我应该穿上外衣,而我给了我的演讲。她也给我带来了杯热茶。有些人似乎警惕直接对我说话。这种微妙的姿态,更加动人。

学员们也没有像龊作为蠢事朝鲜建议。在我的最后一天,我发明了一种游戏,使我们能够讨论朝鲜这样的国家的经济问题,而它实际上是朝鲜。它涉及到一个国家,的“ParadiseIsland”,面临货币危机,通胀猖獗,境况不佳的国有工业,商品价格下跌,以及渐远的北方邻居。它可能是古巴。它也可能是朝鲜。人们分成小组,并告诉岛上的排序问题。然后,他们不得不提名一名发言人解释,在英语,如果可能的话,应该怎样做。

他们的反应会作出IMF自豪的。第一发言人建议国有企业私有化,提高硬通货,促进竞争以提高效率。她的小组提出了提高利率来吸引外来投资。它认为时间的工作力量,以减轻紧缩政策的后果。另一组建议,增值原料,把它们变成理想的成品。第三个建议把在多边机构来帮助通过紧缩驱动器的潮人。我简直不敢相信我所听到的。最重要的,我感到非常震惊如何自由和轻松,他们讲出来。一个年轻人来找我算账,并开玩笑说:“我从来没有意识到我是多么会享受我自己的国家。”这种互动作为一个惊人的提醒是多么宝贵,利用人民对人民的交流与无赖国家像朝鲜可以。任何人(接入互联网)可以到达朝鲜时代Exchange联机。

*我的访问是在3月下旬,但由于写关于朝鲜的敏感性,刊发这篇文章被推迟了几个月。

撤消修改

Alpha

此翻译比原来的更好?

是,提交翻译

感谢您提交的内容。

Jīngxǐ shì bùshì dào cháoxiǎn de yóukè hěn kěnéng jīngcháng yù dào. Zhǐnán, jīngxīn cèhuà de xíngchéng, tōngcháng jiéjìn quánlì, yǐ bìmiǎn yìwài de shuā yǔ pǔtōng de cháoxiǎn rén, wúlùn tāmen shì mài yīfú huò yùmǐ de fùnǚ zài dāngdì de yè fēi “qīngwā shìchǎng”, huò zài dāngdì jiǔbā hējiǔ de nánrén. Zhè shì yīgè chǐrǔ, yīnwèi zhèyàng de zāoyù, bāngzhù yīgè zhīzhī shèn shǎo de rén, rénxìng huà: Lìrú, yīgè 23 suì de cháoxiǎn miǎn tiǎn de gàosu wǒmen, tā shì hútú, zhè kěnéng jìnyībù qù pòhuài dìngxíng bǐ tā yǔ bù lā dé·pítè zuìjìn fǎngwèn Suǒ néng xiǎngxiàng. Lìng rén gāoxìng de shì, yīxiē fēi zhèngfǔ zǔzhī de guǎnlǐ yào túpò zhè zhǒng bù xìnrèn de hòu hòu de miànshā, yǐ cùjìn zhēnzhèng de cānyù yǔ mínzhǔ rénmín gònghéguó (cháoxiǎn). Zǒngbù shè zài xīnjiāpō de cháoxiǎn wángcháo jiāoliú, cùjìn rénmíng duì gāo fēiyáng de niánqīng zhuānyè rénshì hé guānliáo cháoxiǎn hé wàimiàn de shìjiè de rénmen zhī jiān de jiēchù, shì qízhōng zhī yī. *Jìnrì, wǒ qiánwǎng píngrǎng, yǔ tāmen jǔxíng tǎolùn jīngjì yǔ cáizhèng bù hé yāngháng de chéngyuán. Cóng kāishǐ dào jiéshù, wǒ jiēchù nàxiē wǒ chǔlǐ líkāi wǒ chījīng. Ǒu'ěr, wǒ liú xiàle shēnkè yìnxiàng.

Qǐchū, tā shì hěn nán zhīdào shénme shǐ cháoxiǎn de jīnróng jīgòu. Chāochūle wǒ de jiǔdiàn, xīn de zhōngyāng yínháng, gāo yuē 20 céng, zhèngzài xīngjiàn de dàtóng hé de hé'àn shàng. Zài wǒ dàodá zhīqián yǒurén gàosu wǒ kěnéng shì dùzhuàn de gùshì, zhōngyāng yínháng jiāmen zìjǐ zuò de jiànshè gōngzuò. Zài yīgè wài qiáng bèi qī chéng quàngào de gōngzuò yào zuò “yī kǒuqì”, jí yīgè kǒuhào, hěn kuài jiù wánchéngle, xiàng jūnshì xíngdòng. Suízhe huòbì fāngǔn, tōngzhàng shàngshēng hé zēngzhǎng tíngzhì, zhè zhàndòu kǒuhào yuè lái yuè duō dì yìngyòng dào jīngjì xué. Jīnzhèng yún niánqīng de dúcái zhě, quànmiǎn:“Ràng wǒmen zhēngfú de hángyè, xiàng wǒmen zhēngfúle kōngjiān, zhǐ de shì qùnián 12 yuè de chòumíng zhāozhù de wèixīng fāshè. Suǒyǐ, dāng wǒ bǎ wǒ dì dìfāng, dǎizú rénmín dà xuéxí tīng, dīngzhe jǐ shí gè biǎoqíng yánsù de jīngjì juécè zhě zài hòu hòu de dàyī, wéijīn hé shǒutào, wǒ hái yǐwéi shì guójiā guīhuà gémìng miànlín de chōngfēng duì. Wǒ zhīchēng yīgè fēicháng jiānnán de shíjiān.

Rán'ér, ér bùshì chāoguò jīngjì xué jiā de kànfǎ, shìjiè jīngjì tiǎozhàn wǒ, tāmen chōu wǒ de shìshí quèzuò de shìshí. Měi gè huìhuà jiéshù shí, jiāofù de piàojù duì wǒ lái shuō, wúlùn shì zài yīngyǔ huò tōngguò wǒ de fānyì, yǔ láizì shìjiè gèdì de (wǒ cāicè) kěnéng shì yǒuyòng de cháoxiǎn jīhū juéwàng de xūqiú ànlì yánjiū. Zhè dǎozhìle yī zhǒng wéimiào de wǔdǎo, yīnwèi gāi guó zìshēn de jīngjì wèntí de tǎolùn shì yángé de jìnjì. Zìjǐ sìhū shuōle hěnduō:“Nǐ zuì hǎo gàosu wǒmen gèng xiángxì de xiāoxi, qiángliè cuòcí” yī shuō. “Wǒmen xīwàng gèng zhēnshí de lìzi,” lìng yīgè shuō. De wèntí, hěnduō de huàtí jízhōng zài tōnghuò péngzhàng hé huòbì wěndìng jìhuà, dìfāng dāngjú de guānzhù. “Nǐ shì rúhé pínghéng tōngzhàng hé jīngjì zēngzhǎng” yī shuō. “Shénme shì zuì jiā de tōngzhàng lǜ? Shénme shì lǐxiǎng de tōngzhàng mùbiāo shuǐpíng,“lìng yīgè shuō. Lìng yīgè shuō:“Wǒ zài xiànshí zhènhàn bān de jìhuà, yǐ jiǎnshǎo zài 1995 nián mòxīgē tōnghuò péngzhàng hěn gǎn xìngqù. Lìrú, tā shì zěnme máo dìng tōngzhàng yùqí?“Bùzhǐ yīcì, wǒ gàosu tāmen, zhǐyào tāmen yǒu fǎngwèn hùliánwǎng, tāmen kěyǐ zhǎo chū zhèyàng de wèntí běnshēn de dá'àn. Zhè pángménzuǒdào de jiànyì tōngcháng shì huìjiàn liǎng yǎn fā zhí. Dàn tāmen méiyǒu tāmen de lǐlùn zhīshì bùzú, lián wǒ zìjǐ (fēi jīngjì xué jiā) jiěshì: Yīdàn nénggòu tígāo wǒ jiěshì tōnghuò péngzhàng de chéngyīn.

Wǒ qù cháoxiǎn wǔzhuāng wǒ zìjǐ de yīxiē pángménzuǒdào de gōngjù. Jǔlì lái shuō, wǒ rènwéi “jīngjì xué rén” jù wú bà zhǐ shǔ de huàndēng piàn jiāng yúlè, bù zhǐshì wèile yǐnqǐ tǎolùn gòumǎilì píngjià, dàn gèng duō de tǎolùn hànbǎo. (Rúguǒ nǐ xiāngxìn de měi rì kuàisù, yùnxíng píngrǎng wéiyī de hànbǎo jiǔbā de nǚrén shì jīn zhèng rì de āyí, hé hànbǎo bèi chēng wèi “duò suì de ròu huò miànbāo”.) Jīn zhèng rì de fùqīn, jīn zhèng rì jǐngtì de mùguāng xià, hé tā de zǔfù Jīn rì chéng, wǒ tíchū de jù wú bà zhǐshù (jiàn xià tú). Quèshí yǒu màidāngláo de yīgè jiǎnduǎn de tǎolùn. Dàn jǐ rù gèng wèi yǒuqù de shì, zhōngguó de huòbì shìfǒu gāo gū huò dīgū de.

Zhè jiā ānjìng de huòbì hé tōngzhàng de míliàn shì kěyǐ lǐjiě de. Zài cháoxiǎn shēnghuó de tèshū xìng zhī yī shì pǔtōng rén rúhé guǎnlǐ qiú shēngcún, shènzhì zài bǐjiào fánhuá de shǒudū, zài yáchǐ de yī zhǒng yǒuhài de, shìshí shàng de shuāng huòbì xìtǒng. Jù guānfāng tǒngjì, zài wǒ zhù de jiǔdiàn shì 100 hányuán duì měiyuán huìlǜ. Zài chāoshì lǐ mài de yīqiè cóng pīngpāng qiúpāi nèiyī yùshì tàofáng (suǒyǒu cóng zhōngguó jìnkǒu de), yīgè nǚrén zài wǒ miànqián ràng wǒ zhènjīng yóu bōluò jié zhàng piàojù 110000 hányuán. Zhè shí wǒ cái yìshí dào, tā (huīsè shìchǎng) huìlǜ, gùdìng zài yīgè bù xiǎnyǎn de chuāngkǒu hòumiàn jié zhàng, wèi 8000 hányuán duì měiyuán. Jìnkǒu wēidìmǎlā kāfēi yībēi, kěnéng huì huāfèi jǐ yuán qián, wǒ hé tā. Dàn yīgè dàxué jiǎngshī, wǒ gēn, tā huì dàibiǎo chāoguò yīgè yuè de xīnshuǐ de guānfāng huìlǜ shǐyòng hányuán, tā yíngdé. Nánguài tā kěyǐ bù jìde shàng yīcì tā dàizhe yīgè nǚhái chūqù yuēhuì. Tā shuō, tā fēicháng gǎnxiè wùzī jiāo gěi jūwěihuì, shǐ rénmen nénggòu dédào rúcǐ dī de gōngzī zhìdù. Dàn nàxiē shuí nénggòu huòdé měiyuán, yīncǐ kěyǐ mǎi dào piányi de kāfēi, jiǔjīng, shòusī, niúpái hé qìchē, hé nàxiē shuí bù zhī jiān de bù píngděng, shì bǐ dàtóng hé gèng kuān. Hěnduō rén zài wǒ de jiǎngzuò bà báo (suīrán fùnǚmen chuānzhuó wú kě tiāotì). Wǒ wúfǎ zhǎo chū tāmen chī shénme, chī wǔfàn, yīnwèi wǒmen méiyǒu yīqǐ chī.

Háo wú yíwèn, cānjiā yántǎo huì de bùfèn tèquán de jīngyīng, dàn méiyǒu tèquán. Tāmen chuānzhuó chénzhòng de dōngjì chǐlún zài chūn mò, yīnwèi tāmen jiǎnzhí bīng hán tōngguò jiǎngzuò, yīnwèi tāmen zuò zài hǎimián tǐ dàtīng. Zhǐyǒu wǒ huòdéle yī bǐ xiǎo é jiārè qì yào zhùyì bǎonuǎn, zhè shì yǐncáng bèihòu de jiǎngtái. Yī míng chéngyuán de guānzhòng shuí bù zhīdào wǒ yǒu zhège tèquán lái gàosu wǒ, wǒ yīnggāi chuān shàng wàiyī, ér wǒ gěile wǒ de yǎnjiǎng. Tā yě gěi wǒ dài láile bēi rè chá. Yǒuxiē rén sìhū jǐngtì zhíjiē duì wǒ shuōhuà. Zhè zhǒng wéimiào de zītài, gèngjiā dòngrén.

Xuéyuánmen yě méiyǒu xiàng chuò zuòwéi chǔnshì cháoxiǎn jiànyì. Zài wǒ de zuìhòu yītiān, wǒ fāmíngliǎo yī zhǒng yóuxì, shǐ wǒmen nénggòu tǎolùn cháoxiǎn zhèyàng de guójiā de jīngjì wèntí, ér tā shíjì shang shì cháoxiǎn. Tā shèjí dào yīgè guójiā, de “ParadiseIsland”, miànlín huòbì wéijī, tōngzhàng chāngjué, jìngkuàng bù jiā de guóyǒu gōngyè, shāngpǐn jiàgé xiàdié, yǐjí jiàn yuǎn de běifāng línjū. Tā kěnéng shì gǔba. Tā yě kěnéng shì cháoxiǎn. Rénmen fēnchéng xiǎozǔ, bìng gàosu dǎo shàng de páixù wèntí. Ránhòu, tāmen bùdé bù tímíng yī míng fāyán rén jiěshì, zài yīngyǔ, rúguǒ kěnéng dehuà, yīnggāi zěnyàng zuò.

Tāmen de fǎnyìng huì zuòchū IMF zìháo de. Dì yī fà yán rén jiànyì guóyǒu qǐyè sīyǒu huà, tígāo yìng tōnghuò, cùjìn jìngzhēng yǐ tígāo xiàolǜ. Tā de xiǎozǔ tíchūle tígāo lìlǜ lái xīyǐn wàilái tóuzī. Tā rènwéi shíjiān de gōngzuò lìliàng, yǐ jiǎnqīng jǐnsuō zhèngcè de hòuguǒ. Lìng yī zǔ jiànyì, zēngzhí yuánliào, bǎ tāmen biàn chéng lǐxiǎng de chéngpǐn. Dì sān gè jiànyì bǎ zài duōbiān jīgòu lái bāngzhù tōngguò jǐnsuō qūdòngqì de cháo rén. Wǒ jiǎnzhí bù gǎn xiāngxìn wǒ suǒ tīng dào de. Zuì zhòngyào de, wǒ gǎndào fēicháng zhènjīng rúhé zìyóu hé qīngsōng, tāmen jiǎng chūlái. Yīgè niánqīng rén lái zhǎo wǒ suànzhàng, bìng kāiwánxiào shuō:“Wǒ cónglái méiyǒu yìshí dào wǒ shì duōme huì xiǎngshòu wǒ zìjǐ de guójiā.” Zhè zhǒng hùdòng zuòwéi yīgè jīngrén de tíxǐng shì duōme bǎoguì, lìyòng rénmíng duì rénmín de jiāoliú yǔ wúlài guójiā Xiàng cháoxiǎn kěyǐ. Rènhé rén (jiē rù hùliánwǎng) kěyǐ dàodá cháoxiǎn shídài Exchange liánjī.

*Wǒ de fǎngwèn shì zài 3 yuè xiàxún, dàn yóuyú xiě guānyú cháoxiǎn de mǐngǎn xìng, kān fā zhè piān wénzhāng bèi tuīchíle jǐ gè yuè.

“”的用法示例:

由 Google 自动翻译

字典

Would you mind answering some questions to help improve translation quality?

Google 翻译(企业版):译者工具包网站翻译器全球商机洞察

将文件或链接拖放到此处以翻译文档或网页。

将链接拖放到此处以翻译网页。

我们不支持您拖放的文件类型,请尝试其他文件类型。

我们不支持您拖放的链接类型,请尝试其他类型的链接。

关闭即时翻译关于 Google 翻译移动隐私权政策帮助发送反馈

点击可修改和查看其他翻译

按住 Shift 键的同时拖动短语即可重新排序。

SERENDIPITY is not something the visitor to North Korea is likely to encounter often. Guides, with carefully planned itineraries, usually go to great lengths to avoid accidental brushes with ordinary North Koreans, whether they be women selling clothes or maize in the local fly-by-night “frog markets”, or men drinking in local bars. It is a shame, because such encounters help humanise a poorly understood people: for instance, on a recent visit one 23-year-old North Korean told us shyly that she was besotted with Brad Pitt, which probably went further in busting stereotypes than she could have imagined. Happily, some non-governmental organisations are managing to break through this thick veil of mistrust to foster real engagement with the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). Singapore-based Choson Exchange, which promotes people-to-people contact between high-flying young professionals and bureaucrats of the DPRK and the outside world, is one. Recently*, I travelled to Pyongyang with them to hold discussions on economics with members of the finance ministry and central bank. From beginning to end, my contacts with those I dealt with left me surprised. Occasionally, I was deeply impressed.

At first, it is hard to know what to make of the North Korean financial authorities. Outside my hotel, a new central bank, about 20 storeys high, was being built on the banks of the Taedong river. Before I arrived I was told the probably apocryphal story that the central bankers themselves were doing the construction work. On one outside wall was painted a slogan exhorting the work to be done “in one breath”—ie, finished quickly, like a military campaign. With the currency tumbling, inflation rising, and growth stagnant, this battle cry is increasingly applied to economics. “Let us conquer industry like we conquered space,” exhorts Kim Jong Un, the youthful dictator, referring to last December’s infamous satellite launch. So when I took my place at the dais in the Grand People’s Study Hall, staring at a few dozen stern-faced economic policymakers in thick coats, scarves and gloves, I thought I was facing the storm troopers of the state-planning revolution. I braced for a very hard time.

However, instead of challenging me over The Economist’s view of the world economy, they pumped me for facts—hard facts. Each session ended with notes delivered to me either in English or via my interpreter, with almost desperate demands for case studies from around the world that (I surmised) could be useful for the DPRK. This led to a delicate dance, because discussion of the country’s own economic problems was strictly taboo. The strong wording of the messages themselves seemed to say a lot: “You better tell us in more detail,” said one. “We want more real examples,” said another. The topic of the questions—many focused on inflation and currency-stabilisation plans—indicated where the authorities’ concerns lay. “How do you balance inflation and economic growth,” said one. “What is the optimum inflation rate? What is the ideal level for inflation targeting,” said another. Another: “I’m interested in the real shock-like plan to reduce Mexican inflation in 1995. For example, how did it anchor inflation expectations?” More than once, I told them that if only they had access to the internet, they could find out the answer to such questions themselves. That heretical suggestion was usually met with a blank stare. But they had no shortage of theoretical knowledge about them: once, even my own (non-economist) interpreter was able to improve on my explanation of the causes of inflation.

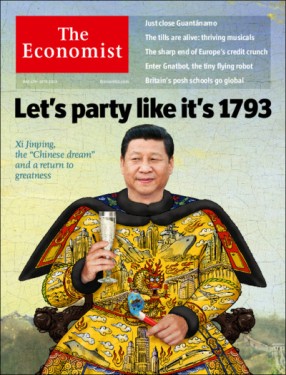

I went to North Korea armed with some heretical tools of my own. For example, I thought a slide of The Economist’s Big Mac Index would be entertaining, not just to elicit a discussion on purchasing-power parity, but more to discuss burgers. (If you believe the Daily Express, the woman who runs Pyongyang’s only burger bar is Mr Kim’s aunt, and the burgers are called “minced meat and bread”.) Under the watchful gaze of Mr Kim’s father, Kim Jong Il, and his grandfather, Kim Il Sung, I presented the Big Mac Index (see picture below). There was indeed a brief discussion about McDonald’s. But far more interesting for the boffins was whether China’s currency was over- or undervalued.

This quiet obsession with currencies and inflation is understandable. One of the peculiarities of life in North Korea is how ordinary people manage to survive, even in the relatively prosperous capital, in the teeth of a pernicious, de facto dual-currency system. Officially, the exchange rate in my hotel was 100 won to the dollar. At a supermarket selling everything from ping-pong bats to lingerie to bathroom suites (all imported from China), a woman in front of me shocked me by peeling off 110,000 won in notes at the checkout. Then I realised that her (grey-market) exchange rate, secured at a discreet window behind the checkout, was 8,000 won to the dollar. A cup of (imported Guatemalan) coffee may cost a few dollars to me—and her. But to one university lecturer that I talked to, it would represent more than a month’s salary at the official exchange rate—using the won that he earns. No wonder he could not remember the last time he took a girl out on a date. He said he was very grateful to the regime for the supplies handed out by neighbourhood committees, which enabled people to get by with such low salaries. But the inequality between those who have access to dollars, and hence can buy cheap coffee, alcohol, sushi, steak and cars, and those who don’t, is wider than the Taedong river. Many people in my lectures were rake-thin (though the women were impeccably dressed). I could not find out what they ate for lunch, because we were not allowed to eat together.

Without a doubt, the seminar’s participants were part of a privileged elite—but not that privileged. They wore heavy winter gear in late spring because they were literally freezing cold in the cavernous hall as they sat through the lectures. Only I was given a small heater to keep warm, which was hidden behind the dais. One member of the audience who did not realise I had this privilege came up to tell me that I should put on a coat while I gave my lecture. She also brought me glasses of hot tea. Some people seemed wary of talking to me directly. That made such subtle gestures all the more touching.

The participants were also nothing like as small-minded as parodies of North Koreans suggest. On my last day, I invented a game to enable us to discuss the economic problems of a country like North Korea, without it actually being the DPRK. It involved a country, “ParadiseIsland”, facing a currency crisis, rampant inflation, ailing state-owned industries, falling commodity prices, and an increasingly distant neighbour to the north. It could have been Cuba. It could also have been North Korea. People were divided into groups, and told to sort the island’s problems out. They then had to nominate a spokesman to explain, in English if possible, what should be done.

Their responses would have made the IMF proud. The first spokeswoman suggested privatisation of the state-owned companies, to raise hard currency, and to foster competition to improve efficiency. Her group proposed raising interest rates to attract inward investment. It argued for time, to mitigate the consequences of austerity on the work force. Another group suggested adding value to the raw materials, by turning them into desirable finished products. A third suggested bringing in multilateral institutions to help tide people through the austerity drive. I could hardly believe what I was hearing. Not least, I was shocked at how freely and easily they were speaking out. One young man approached me afterwards, and joked: “I never realised how much I would enjoy running my own country.” Such interactions serve as a stunning reminder of how valuable, and under-exploited, people-to-people exchanges with pariah states like North Korea can be. Anyone (with access to the internet) can reach Choson Exchange online.

* My visit was in late March, but because of the sensitivity of writing about North Korea, publication of this post was delayed for a few months.

鄧文迪山東人,1999年嫁給傳媒大亨梅鐸。梅鐸現有財產110億美元。

鄧文迪山東人,1999年嫁給傳媒大亨梅鐸。梅鐸現有財產110億美元。

Une tortue géante dans un élevage du parc national des îles Galapagos, en Equateur, le 4 juin 2013 © AFP Rodrigo Buendia

Une tortue géante dans un élevage du parc national des îles Galapagos, en Equateur, le 4 juin 2013 © AFP Rodrigo Buendia