習近平做「帝王夢」

作者: 嚴煌翊

更新於︰2013-06-06趙紫陽時代的常委政治秘書鮑彤說,這「七不准講」中的任何一條,都是違憲的,都是和共和國的本質水火不相容的。要麼廢掉主旋律廢掉「七不准講」,要麼廢除憲法廢除國號,兩者不共戴天。何去何從?看來要做毛澤東第二的習近平是鐵了心了。網上有人就此特作新歌《我的帝王心》一首,借「國母」彭麗媛之口唱出習近平的心聲: 江山常在我夢裡,/體制已多年未改進,/可是不管怎樣也改變不了/我的帝王心。 洋裝雖然穿在身,/我心依然是帝王心;/我的祖宗早已把我的一切/烙上特權印。 潤之、小平、/陳雲、熙來,/在我胸中重千斤。無論何時,/無論何地,/心中一樣親。流在心裡的血,/澎湃著專制的聲音,/就算活在新時代,也改變不了/我的帝王心。 在「七不准講」之下,習近平提出的「中國夢」「復興夢」將一夜回到辛亥革命之前的「帝王夢」,那就是復興到大家跟著皇帝一起做夢、全國只有一個皇帝可以做夢的年代。(嚴煌翊)

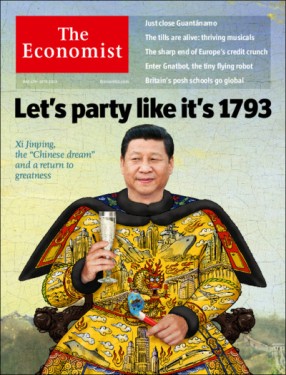

●英國經濟學人周刊封面:讓我們像一七九三年那樣狂歡。編者按:本文報導中共提出「七不講」的來龍去脈。指出前年五不搞到今年七不講,表明毛左思潮已在中共黨內全面回歸,習近平不惜和改革開放背道而馳。

中國一道令人感到詭異不解的奇景:荒誕反動的「七不准講」悍然出台。

近日,網路盛傳中共中央推出「七不准講」禁令,禁止中國媒體和學校教師宣講七個話題,即:普世價值、公民社會、新聞自由、公民權利、黨的歷史錯誤、權貴資產階級、司法獨立。這「七不准講」是從中共高層傳達下來的口頭密令概括整理而成。一個世界人口第一的大國的執政黨,卻以口傳密令的形式發佈牽涉全國十幾億人的基本人權和權利的行政命令;而且這道「密旨」,在中國大陸很多網站上也是不能講不能討論的,講了網站就會被「和諧」微博就會被遮罩。在世界文明史上,這實在是一道令人感到詭異不解的奇景。

七不講內容可謂荒誕不經

但更令人驚訝的是那密令內容本身。有識之士都一致認為,「七不准講」可謂荒誕之極!今天世界上,普世價值、新聞自由和公民權利都是全球絕大多數人的共識。對公民社會一詞,雖有不同理解,但也不應該禁止討論。至於中共歷史上的錯誤,從「反右」、「大躍進」,到「文革」,都已編入現行大學生黨史教材,根本算不上禁忌。說到權貴資本主義,中共既然聲稱堅持社會主義道路,則應該對這個社會主義原則的天敵大講特講,以引起全黨全國人民的反對和制止。而關於司法獨立,中國憲法明文規定法院和檢察院依法獨立行使司法權,司法獨立應該也是社會主義應有之義。

當局推出這七個不能觸及的禁區,實際上反而是在提醒大家,這正是當今中國民眾最關心的中國現今體制上最大的七個弊端。這本該是當政者未來努力改革的重點和方向。但是,現在連講都不能講,這讓那些寄希望於「新人新政」的人情何以堪!網民說,「七不准講」概括起來其實就是一句話——不准講文明。上世紀三十年代,進步文人寫出一副諷刺國民黨專制獨裁的對聯,上下聯:

江山是老子打來,誰讓你開口民主閉口民主?

天下由本黨坐定,且看我一槍殺人二槍殺人!

難道現在時光倒流了嗎?實際上,中共下達的「七不准講」密令讓習近平本人陷入了一種不仁不義、難以自拔的困境。

不准講「黨的歷史錯誤」就將鄧小平置於一種尷尬的境地。因為鄧主導在一九八一年發佈《關於建國以來黨的若干歷史問題的決議》,就是要求全黨要認識中共執政以來的種種錯誤,汲取教訓,不要重蹈覆轍。現在七不講是否要推翻鄧小平的這些觀點?!

再說習近平的父親習仲勳。一九六二年九月,因所謂「《劉志丹》小說問題」被毛澤東以「利用小說進行反黨」這種莫須有的罪名打入「反黨集團」,連未成年的習近平也受到株連。於是,現在問題來了。是不是習近平也不可以說父親是正派人,不是毛一夥所說的「野心家反黨分子」?

七不講來自全國宣傳部長會議

習近平登基之初,為了鞏固自己的地位自然要重拳出擊又要各方照顧,但搞出「七不准講」,看來絕非權宜之計,而是要在意識形態戰線上為自己定於一尊。經過許多人考證,「七不准講」的原型其實就是今年四月底發至縣團級的中辦第九號文件——《中共中央辦公廳印發︿關於當前意識形態領域情況的通報﹀的通知》(「中辦發【2013】9號」),或稱《2013年全國宣傳部長會議紀要》。該文件分三部分:一,情況;二,問題;三,對策。所列的七個問題為:

一、民主與憲政理念:目的是要推翻共產黨領導,推翻社會主義,顛覆國家政權。《南方週末》事件就是明目張膽的挑釁。

二、普世價值:核心是排除黨的領導,要黨讓步。

三、公民社會:要害是在基層黨組織之外建立新的政治勢力。

四、新自由主義:是反對國家進行宏觀調控。

五、西方新聞觀念:是反對黨一貫堅持的「喉舌論」,是要擺脫黨對媒體的領導,搞公開化,用搞亂輿論來搞亂黨、搞亂社會。

六、歷史虛無主義:要害是針對黨領導下的歷史問題,否認人們已經普遍接受的事實。突出表現於極力貶損和攻擊毛澤東和毛澤東思想,全盤否定毛澤東領導時期中國共產黨的歷史作用。目的是削弱甚至推翻黨的領導的合法性。

七、歪曲改革開放:認為出現了官僚資產階級、國家資本主義。認為中國改革不徹底,只有進行政治改革之後,才能進行經濟改革。

而針對這些問題的對策包括:

一,必須堅持「喉舌論」。

二,必須堅持指導思想是馬列毛與特色理論。

三,今後不能允許反馬列毛言論公開地堂而皇之地在媒體上出現,宣傳戰線將清理反黨、反國家、反民族立場的「新三反人員」,「不換立場就換人」。

四,對媒體要加強管理與引導,媒體人要有鮮明的政治立場,要有清醒的政治頭腦,要堅持客觀真實性原則,要對社會負責。不能成天全版面報導負面東西,對正面的卻視而不見。

五,加強黨對媒體輿論的領導,要從培養新聞人才抓起,凡有「新三反」傾向的不准在高校教授新聞專業。

這個二○一三年全國宣傳部長會議,上綱上線,殺氣騰騰,將這些年來所有與中共中央稍有政見不同者統統打入敵對陣營。

習近平不惜與改革開放背道而馳

中辦文件級別雖然次於中共中央文件,但也需要全體常委簽字,已經不單是劉雲山和他的文宣系統的事,顯然是習近平意見的不二發揮。習近平上位之後,提出「兩個不能否定」——「不能用改革開放後的歷史時期否定改革開放前的歷史時期,也不能用改革開放前的歷史時期否定改革開放後的歷史時期。」他崇拜毛澤東,說「否定了毛澤東⋯⋯就會天下大亂」。他要全黨警惕蘇聯解體教訓,說,蘇共解散,「竟無一人是男兒,沒什麼人出來抗爭。」他在二中全會上強調:「意識形態搞不好也會出大問題!這麼多年來大家很少強調這個問題。一些西方國家⋯⋯是想達到分裂中國的目的,想讓中國變顏色!」他提出「三自信」:道路自信、理論自信、制度自信⋯⋯

二○一一年中國兩會期間,時任全國人大委員長的吳邦國曾鄭重表明,中國不搞多黨輪流執政,不搞指導思想多元化,不搞「三權分立」和兩院制,不搞聯邦制,不搞私有化。他並表示,中國這一特色政治文明具備不可動搖的法制根基。這「五不搞」成為中共政改史上一個可恥的標誌,預示了中國民主道路的坎坷。如果說「五不搞」為中國政改定出邊界,那麼如今的「七不講」就是封殺中國最活躍的改革陣地的七把刺刀。習近平以此不惜與開放改革背道而馳。

毛左派活躍喜出望外,彈冠相慶

從「五不搞」到「七不講」,透露出一個非常明確的資訊,那便是毛左思潮將在中共黨內全面回歸!習近平聖旨令下,各路文武紛紛出台,搖旗吶喊,大造輿論。二月二十三日,鷹派將軍羅援在微博上提出「內懲國賊」的口號,目標直指國內主張走憲政之路的自由派。四月十一日,中共陝西省委宣傳部常務副部長、全國記協副主席任賢良,在中共機關刊物《紅旗文稿》撰文《統籌兩個輿論場凝聚社會正能量》,官網及門戶網站均予轉載,殺氣騰騰要規制新媒體,佔領輿論新陣地。四月三十日,重慶警備區司令員朱和平發表文章《要堅守意識形態的「上甘嶺」》。

五月七日,《光明日報》發表中共中央黨史研究室齊彪文章《「兩個不能否定」的重大政治意義》;五月十三日,《人民網》轉載社科院副院長李慎明文章《正確評價改革開放前後兩個歷史時期》,讚賞習近平這「深得黨心、軍心和民心,具有重大意義」的觀點。五月二十一日,人民大學法學院教授楊曉青發表長文《憲政與人民民主制度之比較研究》,核心觀點是「憲政的關鍵性制度元素和理念只屬於資本主義和資產階級專政,而不屬於社會主義人民民主制度」。該文公然挑戰依法治國理念,為專制制度張目。

近日,太子黨及毛左陣營活動頻繁,十分活躍。特別是,去年因為薄熙來事件弄得元氣大傷灰頭土臉的各路毛左分子現在是喜出望外,彈冠相慶。五月五日晚,一場雲集太子黨和毛派分子的「紀念毛澤東誕辰一百二十周年」文藝晚會在山東濟南舉行。這場由毛派名嘴司馬南和孔慶東主持的晚會座無虛席,紅歌嘹亮,高調重現薄熙來主政重慶時推行的「唱紅」場面。五月十五日,知名度高的學者劉小楓在「鳳凰網讀書會」上,公開為文革鳴不平,令人震驚地稱毛為「中國現代的國父」!

中國夢原來是習近平的帝王夢

許多人說,中共最大的法寶,一個是騙另一個是殺。前一陣子,習近平說甚麼「把權力關進籠子」,甚麼「中國夢」「憲法夢」,都是「騙」,現在這個「七不准講」是第二套手法「殺」,赤裸裸的壓制。當下中國大陸意識形態領域是人人自危,一片肅殺景象。發文揭露馬三家女子勞教所駭人聽聞的罪行的《Lens視覺》中槍,體制內宣導憲政民主的《炎黃春秋》也再被警告。一大批宣導民主憲政的知識份子,包括冉雲飛(作家、學者);張雪忠(大學教授);蕭雪慧(大學教授);宋石男(學者);何兵(大學教授);斯偉江(律師);沈亞川(記者);項小凱(學者);吳偉(學者);吳祚來(學者);滕彪(律師、學者);慕容雪村(作家)⋯⋯等等,都已經嚐到壓制的滋味。

五月十八日前後,短短幾天之內,他們在新浪、騰訊、網易和搜狐的微博帳戶都遭遇全線封殺。趙紫陽時代的常委政治秘書鮑彤說,這「七不准講」中的任何一條,都是違憲的,都是和共和國的本質水火不相容的。要麼廢掉主旋律廢掉「七不准講」,要麼廢除憲法廢除國號,兩者不共戴天。何去何從?看來要做毛澤東第二的習近平是鐵了心了。網上有人就此特作新歌《我的帝王心》一首,借「國母」彭麗媛之口唱出習近平的心聲:

江山常在我夢裡,/體制已多年未改進,/可是不管怎樣也改變不了/我的帝王心。

洋裝雖然穿在身,/我心依然是帝王心;/我的祖宗早已把我的一切/烙上特權印。

潤之、小平、/陳雲、熙來,/在我胸中重千斤。無論何時,/無論何地,/心中一樣親。流在心裡的血,/澎湃著專制的聲音,/就算活在新時代,也改變不了/我的帝王心。

在「七不准講」之下,習近平提出的「中國夢」「復興夢」將一夜回到辛亥革命之前的「帝王夢」,那就是復興到大家跟著皇帝一起做夢、全國只有一個皇帝可以做夢的年代。

在共產黨治理之下,中國政治有極大的慣性,一旦向左開動馬達,不撞到極左的絕壁斷難回頭。習近平的「帝王夢」,會越夢越離譜,但肯定也像當年毛澤東妄想充當共產主義世界領袖一樣,落得眾叛親離,以失敗告終。

China's future

Xi Jinping and the Chinese dream

The vision of China’s new president should serve his people, not a nationalist state

May 4th 2013 |From the print edition

IN 1793 a British envoy, Lord Macartney, arrived at the court of the Chinese emperor, hoping to open an embassy. He brought with him a selection of gifts from his newly industrialising nation. The Qianlong emperor, whose country then accounted for about a third of global GDP, swatted him away: “Your sincere humility and obedience can clearly be seen,” he wrote to King George III, but we do not have “the slightest need for your country’s manufactures”. The British returned in the 1830s with gunboats to force trade open, and China’s attempts at reform ended in collapse, humiliation and, eventually, Maoism.

China has made an extraordinary journey along the road back to greatness. Hundreds of millions have lifted themselves out of poverty, hundreds of millions more have joined the new middle class. It is on the verge of reclaiming what it sees as its rightful position in the world. China’s global influence is expanding and within a decade its economy is expected to overtake America’s. In his first weeks in power, the new head of the ruling Communist Party, Xi Jinping, has evoked that rise with a new slogan which he is using, as belief in Marxism dies, to unite an increasingly diverse nation. He calls his new doctrine the “Chinese dream” evoking its American equivalent. Such slogans matter enormously in China (see article). News bulletins are full of his dream. Schools organise speaking competitions about it. A talent show on television is looking for “The Voice of the Chinese Dream”.

In this section

- Xi Jinping and the Chinese dream

- Disaster at Rana Plaza

- Enough to make you gag

- Mend the money machine

- Do it by the book

Related topics

Countries, like people, should dream. But what exactly is Mr Xi’s vision? It seems to include some American-style aspiration, which is welcome, but also a troubling whiff of nationalism and of repackaged authoritarianism.

The end of ideology

Since the humiliations of the 19th century, China’s goals have been wealth and strength. Mao Zedong tried to attain them through Marxism. For Deng Xiaoping and his successors, ideology was more flexible (though party control was absolute). Jiang Zemin’s theory of the “Three Represents” said the party must embody the changed society, allowing private businessmen to join the party. Hu Jintao pushed the “scientific-development outlook” and “harmonious development” to deal with the disharmony created by the yawning wealth gap.

Now, though, comes a new leader with a new style and a popular photogenic wife. Mr Xi talks of reform; he has launched a campaign against official extravagance. Even short of detail, his dream is different from anything that has come before. Compared with his predecessors’ stodgy ideologies, it unashamedly appeals to the emotions. Under Mao, the party assaulted anything old and erased the imperial past, now Mr Xi’s emphasis on national greatness has made party leaders heirs to the dynasts of the 18th century, when Qing emperors demanded that Western envoys kowtow (Macartney refused).

But there is also plainly practical politics at work. With growth slowing, Mr Xi’s patriotic doctrine looks as if it is designed chiefly to serve as a new source of legitimacy for the Communist Party. It is no coincidence that Mr Xi’s first mention of his dream of “the great revival of the Chinese nation” came in November in a speech at the national museum in Tiananmen Square, where an exhibition called “Road to Revival” lays out China’s suffering at the hands of colonial powers and its rescue by the Communist Party.

Dream a little dream of Xi

Nobody doubts that Mr Xi’s priority will be to keep the economy growing—the country’s leaders talk about it taking decades for their poor nation to catch up with the much richer Americans—and that means opening up China even more. But his dream has two clear dangers.

One is of nationalism. A long-standing sense of historical victimhood means that the rhetoric of a resurgent nation could all too easily turn nasty. As skirmishes and provocations increase in the neighbouring seas (see Banyan), patriotic microbloggers need no encouragement to demand that the Japanese are taught a humiliating lesson. Mr Xi is already playing to the armed forces. In December, on an inspection tour of the navy in southern China, he spoke of a “strong-army dream”. The armed forces are delighted by such talk. Even if Mr Xi’s main aim in pandering to hawks is just to keep them on side, the fear is that it presages a more belligerent stance in East Asia. Nobody should mind a confident China at ease with itself, but a country transformed from a colonial victim to a bully itching to settle scores with Japan would bring great harm to the region—including to China itself.

The other risk is that the Chinese dream ends up handing more power to the party than to the people. In November Mr Xi echoed the American dream, declaring that “To meet [our people’s] desire for a happy life is our mission.” Ordinary Chinese citizens are no less ambitious than Americans to own a home (see article), send a child to university or just have fun (see article). But Mr Xi’s main focus seems to be on strengthening the party’s absolute claim on power. The “spirit of a strong army”, he told the navy, lay in resolutely obeying the party’s orders. Even if the Chinese dream avoids Communist rhetoric, Mr Xi has made it clear that he believes the Soviet Union collapsed because the Communist Party there strayed from ideological orthodoxy and rigid discipline. “The Chinese dream”, he has said, “is an ideal. Communists should have a higher ideal, and that is Communism.”

A fundamental test of Mr Xi’s vision will be his attitude to the rule of law. The good side of the dream needs it: the economy, the happiness of his people and China’s real strength depend on arbitrary power being curtailed. But corruption and official excess will be curbed only when the constitution becomes more powerful than the party. This message was spelled out in an editorial in a reformist newspaper on January 1st, entitled “The Dream of Constitutionalism”. The editorial called for China to use the rule of law to become a “free and strong country”. But the censors changed the article at the last minute and struck out its title. If that is the true expression of Mr Xi’s dream, then China still has a long journey ahead.

China's future: Xi Jinping and the Chinese dream | The Economist

没有评论:

发表评论